By Marine Laouchez

Awans, Belgium: Chuao, Baracoa, Hacienda Rio Peripa: when it comes to cocoa beans, it turns out there are vintages, says Belgian chocolate maker Benoit Nihant.

In a country where chocolate is a source of national pride, Nihant is one of around a dozen "bean-to-bar" makers who go direct to the source in Africa, the Americas and Asia to get the best possible taste.

And it is the Chuao plantation on Venezuela's Caribbean coast, where the beans dry beneath the sun in the village square before a blue and yellow church, that produces the finest chocolate in the world, experts say.

The select group including Nihant and his fellow Belgian Pierre Marcolini are now trying to transform the often traditional world of chocolate making by mastering the process from the bean harvest to the creation of elaborate confections.

"It took us three or four years to really master, to understand the impact of the work on the plantations on the chocolate itself," says the 41-year-old Nihant at his shop in Awans, near Liege in southern Belgium.

After starting out as an iron and steel engineer in the Belgian rustbelt, Nihant says he had a revelation just before he turned 30.

"I suddenly realised that I hadn't chosen my career, my destiny," he says. "I really wanted to create something, and to live my passion on a daily basis."

'Chocolate is made with love'

That passion was chocolate, accounting for the attention to detail that now informs his work.

"Good chocolate is made with love. Good chocolate is made with beans which come from a small plantation, which have been chosen and not mixed with the harvest from a neighbouring plantation," he explains.

"It's chocolate where the grower is aware of what the chocolatier wants and respects all the steps of fermentation and drying without taking shortcuts."

Most of the world's major chocolate makers buy their chocolate ready-made from a small group of multinational firms which mix beans from different sources for a more consistent taste.

But for his chocolate, Nihant has hand-picked nine plantations after a series of journeys, in Venezuela, Ecuador, Cuba, Madagascar and Bali in Indonesia. Soon he hopes to source beans from Peru, where he recently bought land.

He imports 25 tonnes of beans a year in a country that produces a massive 650,000 tonnes of chocolate a year, mostly by big brands including Godiva, Leonidas and Neuhaus.

Going direct to the source does not come cheap, though. He buys his beans for between six and 12 euros ($6.50 to $13) per kilogramme, whereas ready-made chocolate is sold to manufacturers for 3.50 euros per kilo.

Chocolate fans pay the price in the end for their pleasure: a 50-gramme (nearly 2-ounce) Benoit Nihant bar costs between 4.20 euros and 7.20 euros.

- Changing tradition -

It's not just the cocoa beans that have been taken back to their roots.

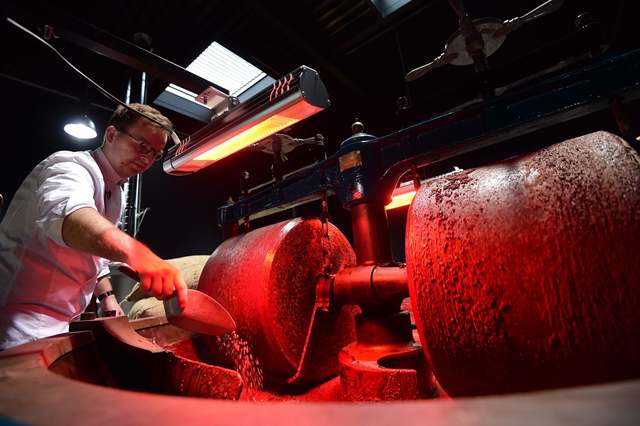

Behind a big window in his workshop, watched by curious customers, are two huge machines.

One dates from the 1950s and was rescued from an abandoned chocolate factory in Asia. The other, for grinding, has two huge granite wheels which turn the roasted and crushed beans into chocolate liquor, the base for all recipes.

The machine dates from the 19th-century and was being used as a decoration in a factory in Greece, but was restored thanks to the know-how of Belgian workers.

"These are the techniques which give you flavour," Nihant says.

It is the operator's job to determine when the cooking process is finished, a crucial yet precise step which extracts the taste from the cocoa.

It's this process that allows Nihant to make a 70 percent dark chocolate that has strong taste without the bitterness.

The chocolatier has made his own expertise the centrepiece of his Christmas window display: five stars representing each of the "grand cru" or major "vintages" of chocolates that he makes.

The one in the middle is stuffed with praline made with lightly salted pecans.

Nihant started off his business in the garage of his parents-in-law and in 10 years he has expanded three times.

Today, he has four shops in Belgium while his chocolate is also sold in around a dozen shops in Japan and is in talks to open in China and the United States, as well as a tie-in with the famed Harrods department store in London.

"We are a generation which is turning tradition and the old way of doing things on its head. We're doing our bit for the Belgian tradition," he says.

AFP